Engaging the public in outcomes-based decision making

Our second evidence session hosted another diverse range of speakers and yet still managed to develop a coherent narrative that connected the thoughts of the speakers. It was encouraging how well it built on the insights from the last session, where we explored how wellbeing is understood and drives (or does not drive) decision making in infrastructure. It also highlighted some key themes about working across scale, different agencies and time that we hope to address in more detail in the next evidence session. As always, this blog is an immediate reflection of the key themes of the discussion, rather than detailed analysis. More formal analysis of all evidence sessions will be provided in the first report expected in early winter.

In this session, we focussed more on the process and outcomes of decision making. There was wide consensus on the need for outcome-driven decision making, rather than decision making that was designed to deliver specific assets or monetary value. There was also a strong theme about the need for strong and early engagement of the public to legitimise these outcomes and improve the effectiveness and delivery of the projects which stemmed from them. These two principles inherently require an evolution in the way we measure value and in the process of decision making, which in turn requires new ways of working collaboratively. These themes will be discussed in more detail below.

Outcome-driven decision making

The potential of infrastructure projects to deliver wider forms of value to improve social and environmental outcomes, as well as economic outcomes is widely acknowledged. However there is limited capacity to articulate and capture these less tangible forms of value. This means that these outcomes are often excluded from decision making processes and the potential is lost at the expense of projects and assets that maximise economic value.

Efforts have been made to monetise these less tangible outcomes using techniques such as Social Return on Investment, which can make them easier to include in traditional appraisal processes. However, these techniques face criticism because of the monetisation and comparison of inherently subjective outcomes can be very difficult. Nevertheless there is a need to more effectively articulate the less tangible forms of value so that they can be better represented in decision making processes.

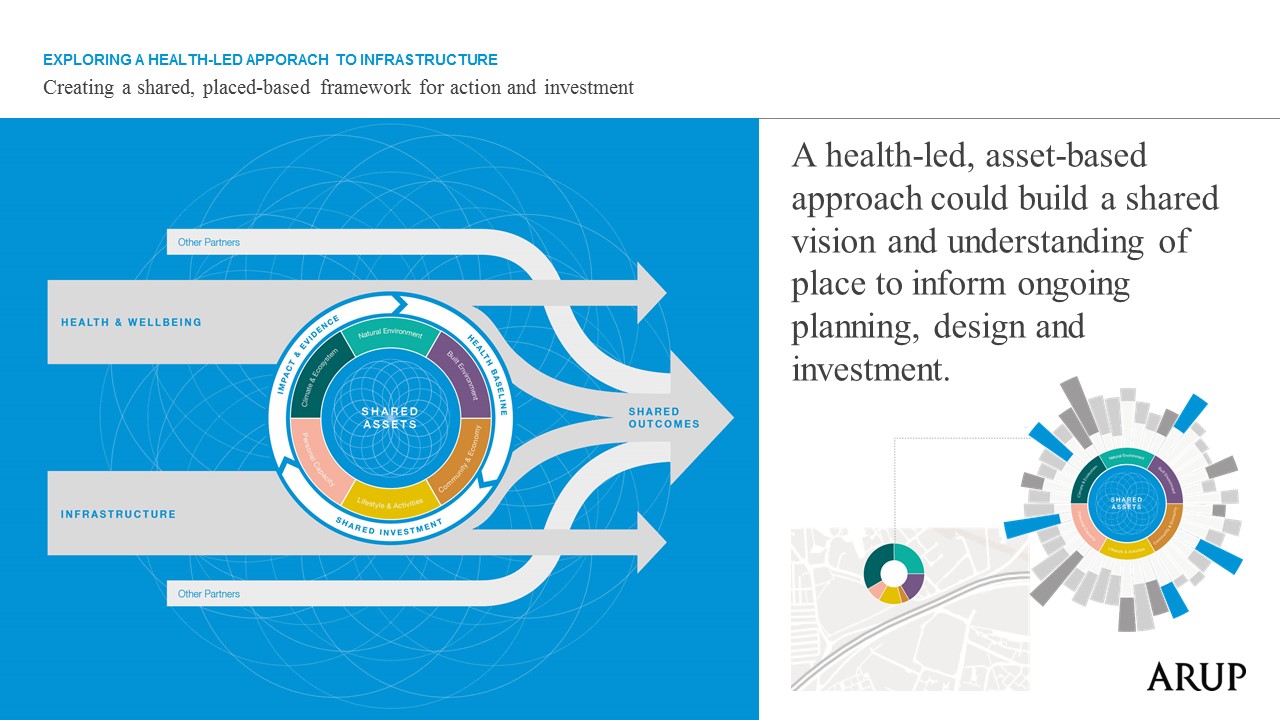

Paul Simkins presented a really useful framework for developing place-based outcomes that articulated a shared vision and understanding of place to inform ongoing planning, design and investment. These outcomes would be far broader than traditional economic metrics of success and include physical and non-physical outcomes, such as self-confidence and connection with societal issues, which align very well with the discussions of social value in this session and of wellbeing in the first evidence session. If these outcomes were defined collectively then investment could be used more effectively across sectors to deliver on the outcomes, exemplified in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Shared outcome-based decision making

Some cities, for example Newcastle and Sheffield are using this approach with the aim to better co-ordinate investment across the city and to ensure that projects are better connected to overarching place-shaping. This place-based approach could also more effectively shape cities' and regions' responses to devolution of power and funding. Outcomes-based regulation is also part of a major reform at the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency, which has been instituted because of the challenges of anticipating technological change and sectoral complexity. Focussing on outcomes, rather than supporting particular projects can help overcome these issues of uncertainty and complexity.

Public engagement

The engagement of the public in deliberating and defining place-based outcomes could greatly increase the transparency and legitimacy of decision making around infrastructure. Ragne Low cited examples where citizen's juries had been set up to develop principles around wind farm development. Researchers found that such juries were able to debate complex issues and manage trade-offs to come to a collective view of principles, despite a wide disparity of views about the topic under debate. Furthermore, experiencing the deliberative process fostered jurors’ civic skills, confidence and sense of self-efficacy, contributing to improvements in wellbeing.

If outcomes are collectively agreed then there is less likely to be resistance to projects which can demonstrate contribution to these outcomes. This can reduce opposition and the costs and delays associated with that opposition. But public engagement should not be deployed solely for reasons of project efficacy; there are strong moral and ethical reasons for giving the public a say in infrastructure decisions.

The Institute for Government has proposed that a new body be created for public engagement - the Commission for Public Engagement - based on the Commission Nationale du Débat Public in France (link here for those who can read french). It argues that more effective public engagement would reduce costly delays and improve the quality of projects by giving people a genuine opportunity to influence decisions. This is proposed predominantly for major infrastructure projects but this model could equally apply to the local scale.

A key aspect of public engagement in decision making is transparency; about what is being debated and what will happen after the engagement. Transparency about the scope of issue under debate is crucial - if a project is being debated but options for change are limited because the planning guidance underlying that project is already set, it is important that those being engaged are aware of this. Transparency about how the results of debate will be used is also critical. Having a debate is very useful but if it is not clear how the findings of that debate get embedded in policy or decisions it can actually disenfranchise the public, reduce legitimacy of decision makers and lead to poor engagement in the future. We need to think carefully about how we use public knowledge to inform decision and to be transparent about the extent to which public knowledge will be used.

The timing of engagement is also crucial - if it is too late in a process there is very little that the public can change or influence, which not only excludes the possibility to improve a project or strategy but also builds up resentment about the validity of engagement. Early engagement is particularly important to understand who infrastructure is being designed for and to articulate less tangible and more subjective outcomes, that might be missed if different stakeholders are not consulted.

Evolution of valuation and appraisal processes

Developing infrastructure to deliver a broader range of outcomes, which include less tangible and more subjective outcomes, requires a very different approach to valuation and decision making. However, it is highly unlikely that valuation and appraisal processes will change overnight. The current systems are deeply entrenched and widely accepted by decision makers so methods will more likely need to evolve to balance the challenge of articulating a wide range of outcomes with the desire to have a consistent process to allow for comparison and evaluation. Some of they insights from the evidence session relating to how decision making process might need to evolve are summarised below:

The notion of value requires greater attention; it is frequently reduced to economic 'value', which excludes a wide range of other outcomes that do not lend themselves so well to monetisation. This includes many of the aspects of wellbeing that we discussed in the last session as well as social value. A more open debate is needed about what we mean by value and how we articulate and capture many different forms of value. The definition of value in any project or strategy is heavily dependent on where in the system value is defined - which further highlight the importance of engaging broadly with stakeholders when defining system outcomes. Following early consultation on defining value, it may be necessary to start with greater extent of quantification of less tangible forms of value or outcomes, to allow us to capture them within current appraisal approaches, while those too evolve.

The apportionment of value or outcomes between groups or organisations also needs to be addressed. Many appraisal processes are only able to capture value that is returned to the organisation investing in the project. This means that value apportioned to another organisation or sector could be 'lost' from the system and therefore excluded from appraisals. This issue also occurs across scales, where value might be apportioned to other cities, regions or the nation; and across time, where value might be created in the future. These issues will be explored in more detail in the next evidence session.

Changing valuation and appraisal processes to be more conducive to outcome-oriented or wellbeing-driven decision making requires a very different skill set. This is beyond the new engineering skills required to design 21st century infrastructure, to those required to engage the public effectively and understand and manage different forms of value. Developing these skills requires training people to analyse systems and undertake critical analysis. It also requires an increase in collaborative skills and the ability to combine knowledge from practitioners with that of the public.

The scale at which decisions are taken matters a great deal. It is becoming widely acknowledged that a greater devolution of decision making on infrastructure would more effectively meet local needs. However, the fear that there is a lack of capability and capacity at the local and regional scale means this is being side-stepped and there is but no real plan to address this. We need a better plan for how to phase the transition of power and spending. Devolution of decision making could also help to overcome the problem of siloed decision making by moving to a more place-based approach. This has been effectively demonstrated in examples such as Sheffield City Region's Integrated Infrastructure Plan, which we will hear more about next month.

Decision making processes need evolve to enable them to take the uncertainty of evidence and forecasts into account. this requires decision makes to build in error and to give discretion to adapt and evaluate. Experimentation and adaptation represent significant challenges to the very risk averse and success oriented approach to decision making and would require significant change in appraisal and evaluation processes. A recent and high profile proponent of this was the Munroe report on Child Protection, which called for a more systemic approach to decision making that addressed the systemic causes of failure, rather than focussing on individuals.

We need to recognise the significant influence of political or personal drivers of decision making. The rules that individuals and organisations make in order to navigate decision making in the face of complexity are rarely explicit or documented. It is important this internal logic is better understood, particularly so that we can better co-ordinate decisions between organisations with very different decision logics. this obviously presents challenges when the implicit drivers could be unpalatable to stakeholders and puts decision makers at significant risk of challenge.

The problem of institutional memory, remembering how and why decisions were taken and what was learned from the process of analysis and evaluation, matters a great deal. A great deal of time and money can be wasted repeating mistakes or gathering evidence, which could be avoided if decision making processes could be recorded more effectively. This is exacerbated by the lack of explicit recognition of decision drivers, which may not be captured in documented appraisal processes. Being more open about this institutional memory could also challenge lock-in by exposing the unwritten assumptions that prioritise certain options and strategies.

These issue represent significant challenges for decision making processes but we hope to learn from some successful cases in the next evidence session to identify some clear recommendations for how they can be addressed.